Introduction

Fire sprinkler systems are still considered one of the most important life safety precautions in modern structures, having been credited with saving lives and limiting property damage across the United States. However, thorough information on their real-world performance and causes of failure has not always been readily available—until now. This blog examines the outcomes of fire sprinkler systems over a five-year period (2019-2023), utilising incident reports from the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS). This analysis provides significant insights for contractors, fire professionals, and AHJs seeking to improve fire protection dependability through better design, installation, and maintenance, ranging from understanding how frequently sprinklers run successfully to identifying key causes of system failure.

Data on Fire Sprinkler System Performance and Failures

While many fire safety supporters have long recognised the benefits of sprinklers, comprehensive methods and data to document their efficiency have not always been easily accessible. Most fire sprinkler training addresses critical technical installation criteria, but this edition examines sprinkler performance from a “30,000-foot” perspective.

Fire sprinkler system installation is becoming more widespread as national building and fire rules recognise their usefulness in protecting both property and lives. This TechNotes will examine fire sprinkler performance during a recent five-year period (2019-2023), focusing on indicators such as the number of sprinklers triggered, fire spread containment, and financial loss reduction.

The causes of fire sprinkler ineffectiveness and failures will be identified, allowing contractors and AHJs to take proactive steps to improve sprinkler reliability during installation and continuing inspection, testing, and maintenance.

This analysis is based on data from the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS), which is handled by the United States Fire Administration. It is believed that 70-75% of the country’s fire departments send incident response data to NFIRS.

Data about the performance and failures of fire sprinkler systems.

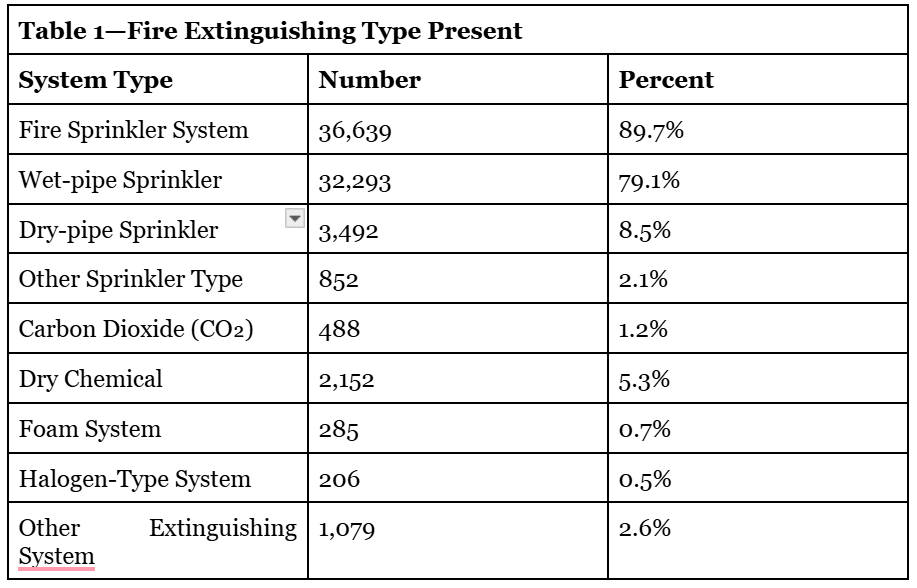

Types of Fire Extinguishing Systems Present

Between 2019 and 2023, there were 66,873 fires in the United States where a fire extinguishing system was present in the building. Because 26,024 events had incomplete data, the type of system could not be determined. Where a fire extinguishing system type was recognised, fire sprinkler systems were by far the most prevalent.

Fire Sprinkler Presence and Performance

As stated in Table 1, there were 36,639 fires with fire sprinkler protection. There were 35,715 full sprinkler systems and 924 partial systems. Data on the performance of complete fire sprinkler systems was supplied for about 19,715 incidents (54%).

Sprinkler performance belongs to one of seven categories:

- Failed to operate

- Fire is too little to operate.

- The system is operational and effective.

- Operated but not effective.

- Operation of AES and other

- Undetermined

- Blank

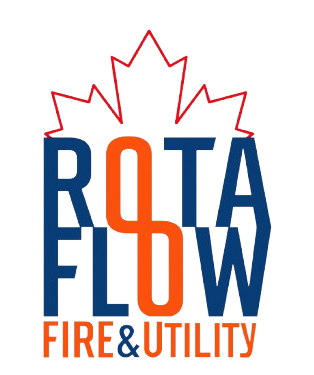

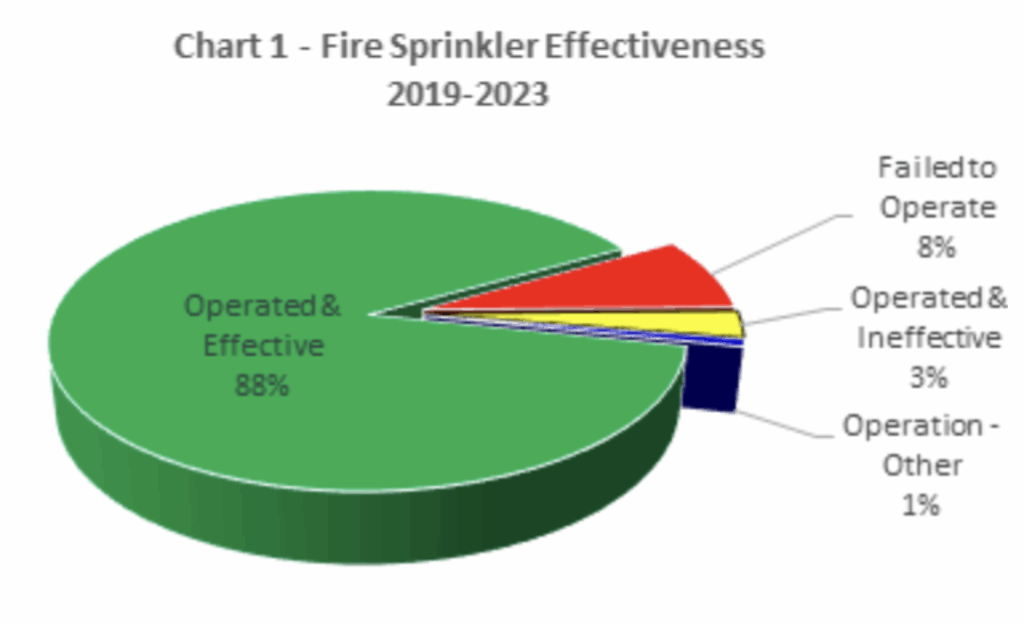

When the three categories that provide no information on sprinkler performance are removed (fire too small to operate, indeterminate, and blank), the effectiveness of fire sprinklers is displayed in Chart 1.

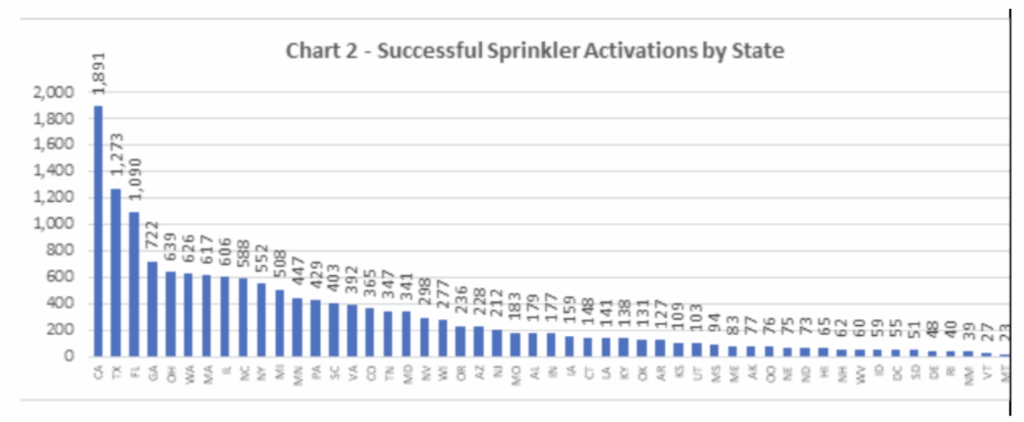

There were 15,710 building fires where sprinklers were successful. Chart 2 displays successful sprinkler activations by state, including the District of Columbia. The “OO” label most likely refers to federal buildings or incidents in which the state of fiorigin was not specified.

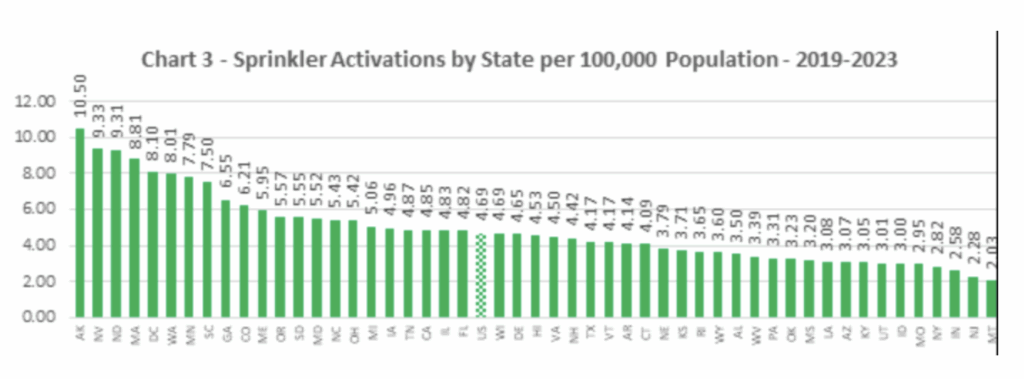

Because there are significant differences between states in terms of size and population, it is often useful to examine events on a per capita basis. Chart 3 depicts successful fire sprinkler activations by state, based on 100,000 people. The United States had 4.7 successful sprinkler activations per 100,000 individuals, which amounts to approximately one fire sprinkler save per 100,000 people per year.

Fire Sprinkler Activations

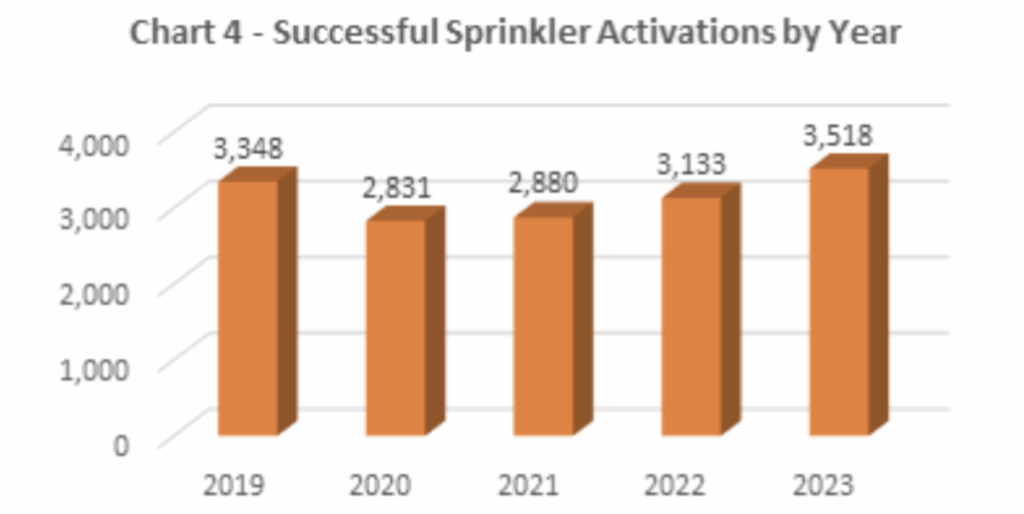

For the last five years, there have been about 3,140 successful sprinkler activations reported to NFIRS, as illustrated in Chart 4.

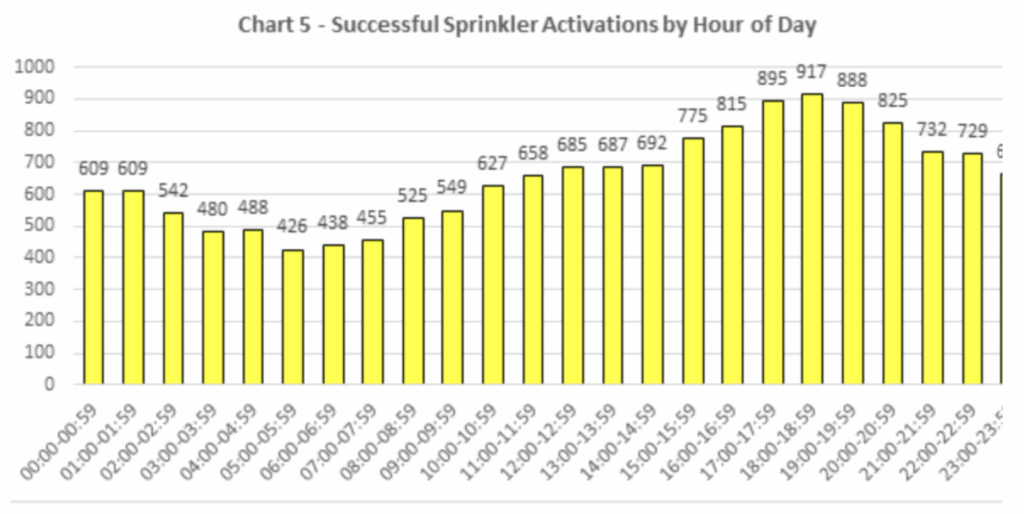

Chart 5 depicts the times of day when fire sprinklers are successfully activated. As can be observed, the most prevalent times are around dinnertime, and the fires are most likely cooking-related.

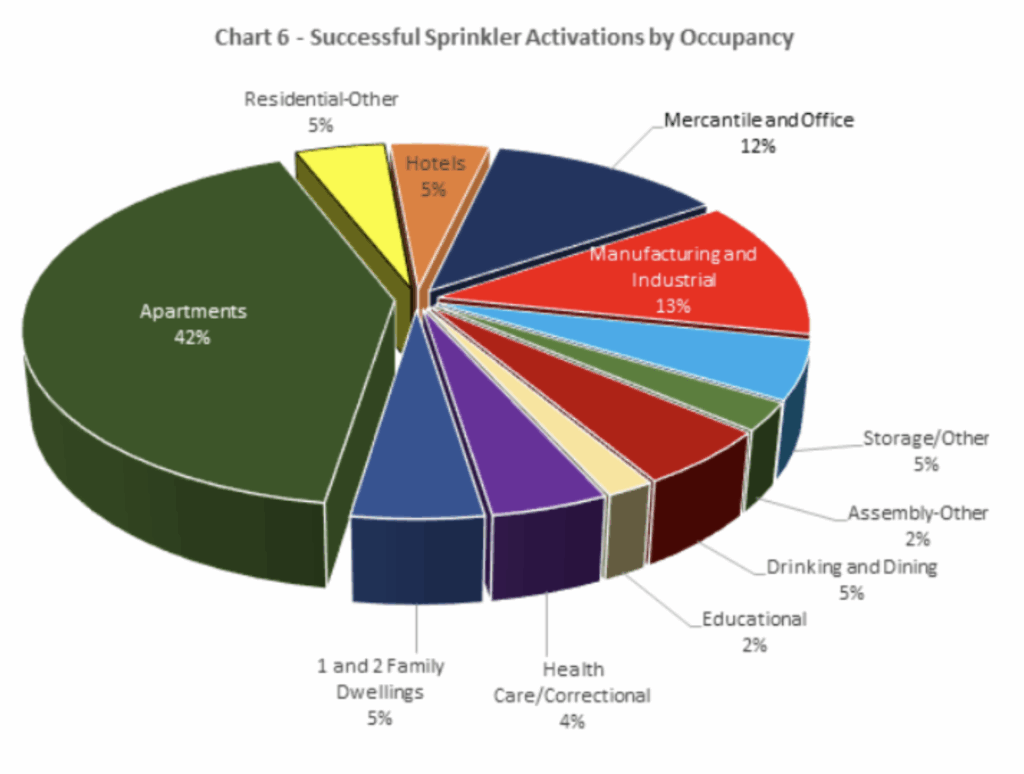

Chart 6 shows the occupancies for successful sprinkler activations. Residential occupancies (apartments, hotels, residences, and other residential buildings) accounted for 57% of all successful fire sprinkler activations during the course of five years.

Performance and Effectiveness

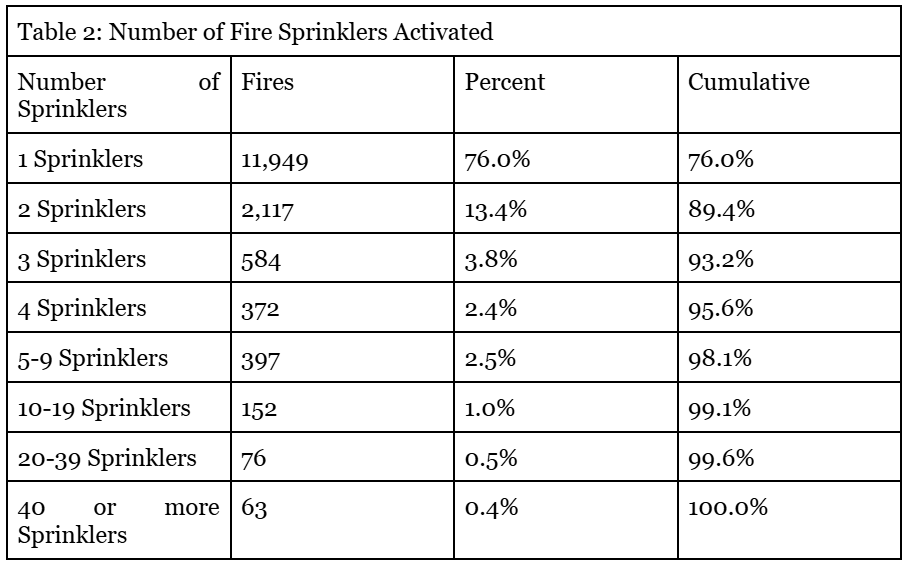

The majority of fires when sprinklers were effective had a small number of sprinklers activated most of the time. Table 2 indicates the number of sprinklers used to extinguish and control the fire.

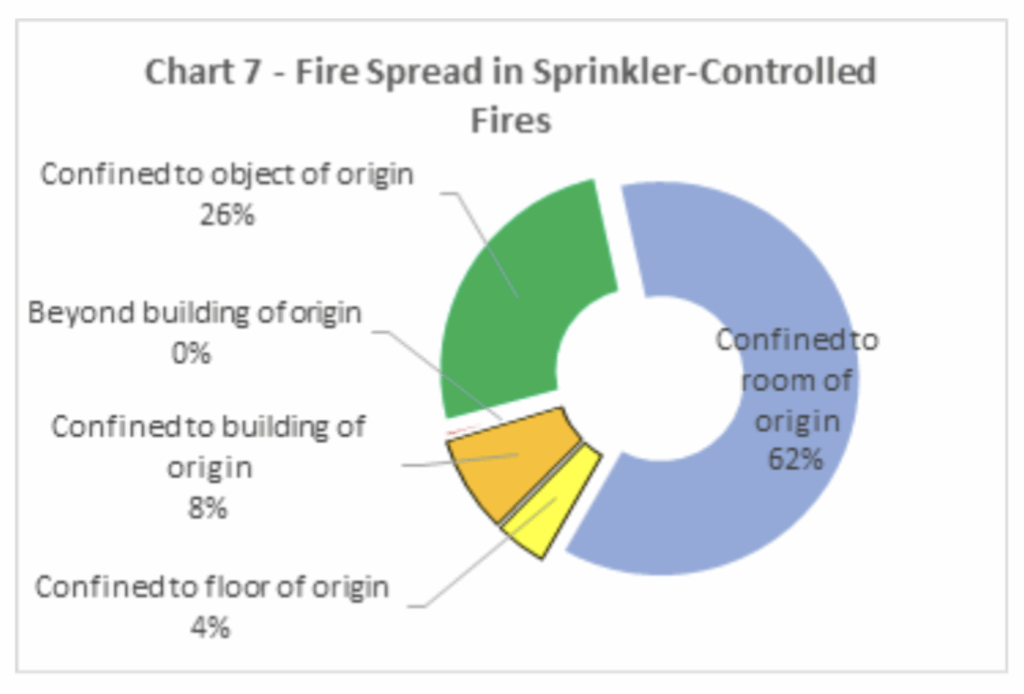

When sprinklers were triggered and managed, fire spread was contained to the object or room of origin in 88 percent of instances, confirming fire sprinklers’ major life safety benefits. When a fire spreads to bigger sections of a building (limited to the building of origin), it frequently begins outside the building or in rooms or areas without fire sprinkler protection. Chart 7 depicts fire spread in sprinkler-controlled fires.

Fire Sprinklers Operated but Were Not Effective

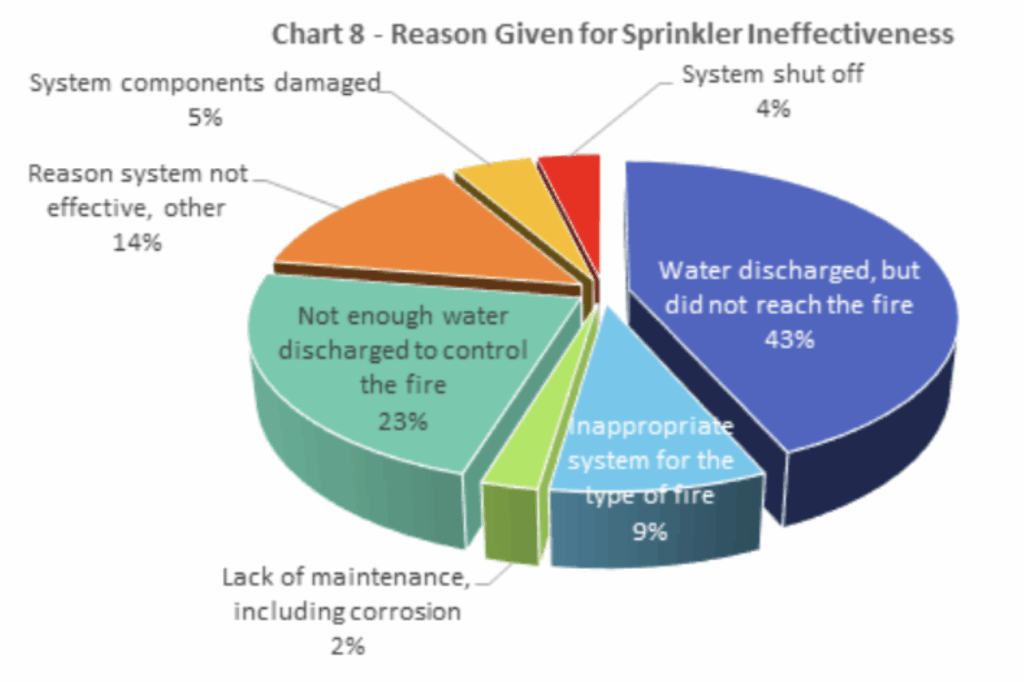

There were 690 fires in which fire department reports showed that sprinklers were operational but ineffective. The seven causes depicted in Chart 8 remain after removing the incomplete, blank, or indeterminate entries.

Sprinklers Failed to Operate

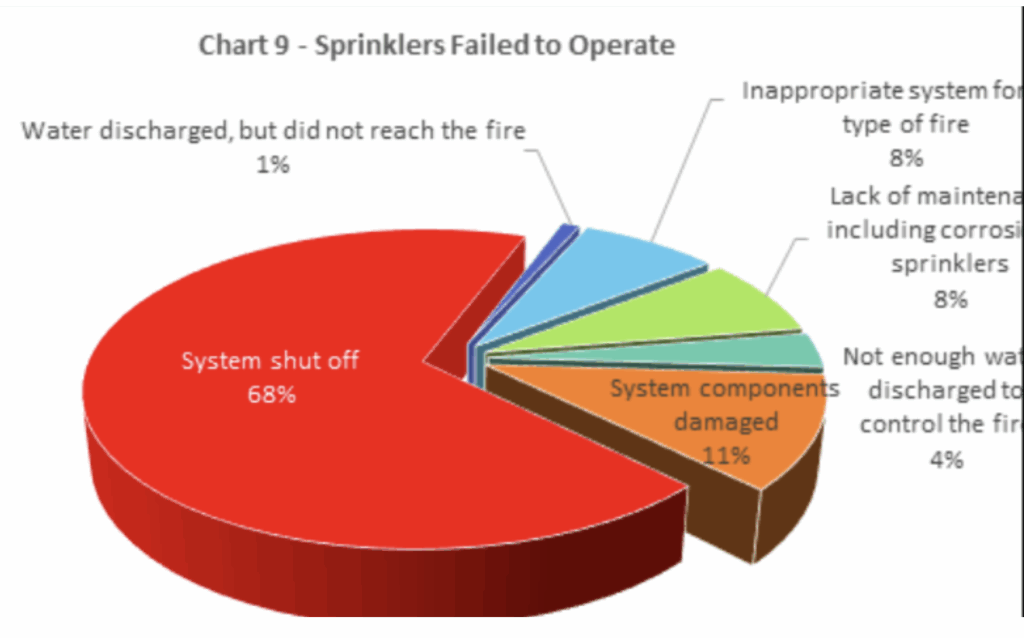

Sprinklers “failed to operate” in 3,171 incidents; however, in over 1,200 fires, the explanation was reported as “fire not in area protected by the system” or “manual intervention defeated the system.” Neither of these conditions can be attributed to sprinkler failure; they were either not present, or the system was turned off before it could be activated.

There were hundreds more cases with the cause indicated as “undetermined” or blank. An apparent software fault or reporting anomaly from a large city stated that nearly all sprinkler activations failed for “other reasons”.

This leaves around 480 reasons why sprinklers fail to perform. Chart 9 depicts the identified causes of sprinkler system failures.

Explanations for Sprinkler Failures or Ineffectiveness

As can be observed, the main cause stated for sprinkler failures (more than two-thirds of the time) is that the system was turned off. This could be the sprinkler system control valve on the riser assembly, or another valve that regulates the water flow to the fire sprinkler system.

These incident reports are being completed by responding fire service members and are based on their observations.

Where “water discharged but did not reach the fire,” it is likely that firemen noticed that the sprinklers were activated but that something was preventing the water from reaching whatever was burning. This could have been a building feature that blocked sprinkler spray or another building component that prevented water from reaching the fire.

There are a few plausible explanations for “not enough water discharged to control the fire”:

- There were too many sprinklers operating.

- A physical impediment in the piping or sprinkler reduced or impeded the water spray.

- The valve in question was partially closed.

- The system was significantly under-designed.

Fire sprinklers may not always be the best option for a fire extinguishing system, albeit this is uncommon. These can include water-reactive compounds or molten metals. This could explain cases where the rationale provided was “inappropriate system for the type of fire”.

The causes of “components damaged” and “lack of maintenance” are generally self-explanatory; however, examples could include items like:

- Physical damage to the sprinkler prevents an effective discharge pattern

- The corrosion of sprinklers

- Sprinklers were painted

- Collapse of building structural components or sprinkler supports before adequate fire extinguishment.

Summary

Fire sprinklers operated and controlled the majority of the fires in which they were present, and the fire was large enough to trigger them. Sprinkler activations were most common in residential buildings, with sprinkler-controlled fires occurring most frequently during supper hours. The fires are most likely triggered by cooking operations.

A minimum quantity of fire sprinklers were used to control the fire. Furthermore, fire sprinklers were extremely efficient in confining fire spread to the object of origin or room of origin, minimising damage and lowering the danger of death to building inhabitants.

Where fire sprinklers were found to be inefficient, the most common explanations provided were that water could not reach the fire and that insufficient water was discharged.

When fire sprinklers failed to operate, the primary reason stated was that the sprinkler system’s water supply had been turned off.

Courtesy: Jon