Introduction: Saying “keeping the home fires burning” makes one picture warmth and family unity. But a real fire raging in your house presents a far different picture, one of terror, damage, and perhaps loss. Residential fires, the most common kind of building fire in the United States, sadly cause the greatest casualties and property damage.

Even if early warning depends on smoke detectors, they cannot put out flames. Residential fire sprinklers become life-saving heroes here. These automatic devices are about giving you and your loved ones priceless seconds to flee a deadly fire, not only about property protection.

Let’s go deeply into the realm of home fire sprinklers. From their early 19th-century beginnings to their contemporary developments, we will examine their history. We will contrast them with commercial fire sprinklers and investigate the studies demonstrating their efficiency in suppressing flames in houses. Real-world data will reveal how sprinklers greatly lower fire deaths, injuries, and property damage; statistics on household fire losses will clearly show the risks we live with.

This article is therefore for you if you have ever questioned if home fire sprinklers are worth the cost. We will address all of your questions and demonstrate why these little tools might make all the difference between a small annoyance and a catastrophic fire. Let’s cooperate to maintain safe, not destructive, burning of the home fires.

To prevent home fires from spreading, use residential fire sprinklers

A patriotic song promoting people to “keep the home fires burning” existed back in World War I. With expectations that the war would finish and everyone would safely return to the conveniences of their home, it was meant to inspire support for the armed services fighting overseas. Of course, a house fire was most likely a calm evening gathering around a fireplace 100-plus years ago. The idea of a home fire now evokes somewhat distinct ideas.

The most commonly occurring form of building fire is a residential one. They cause the greatest harm and kill and hurt most people. Home fire loss statistics will be reviewed here, historical background on home fire sprinklers will be examined, the expansion of the residential sprinkler market will be discussed, and the performance and effectiveness of residential fire sprinklers will be evaluated.

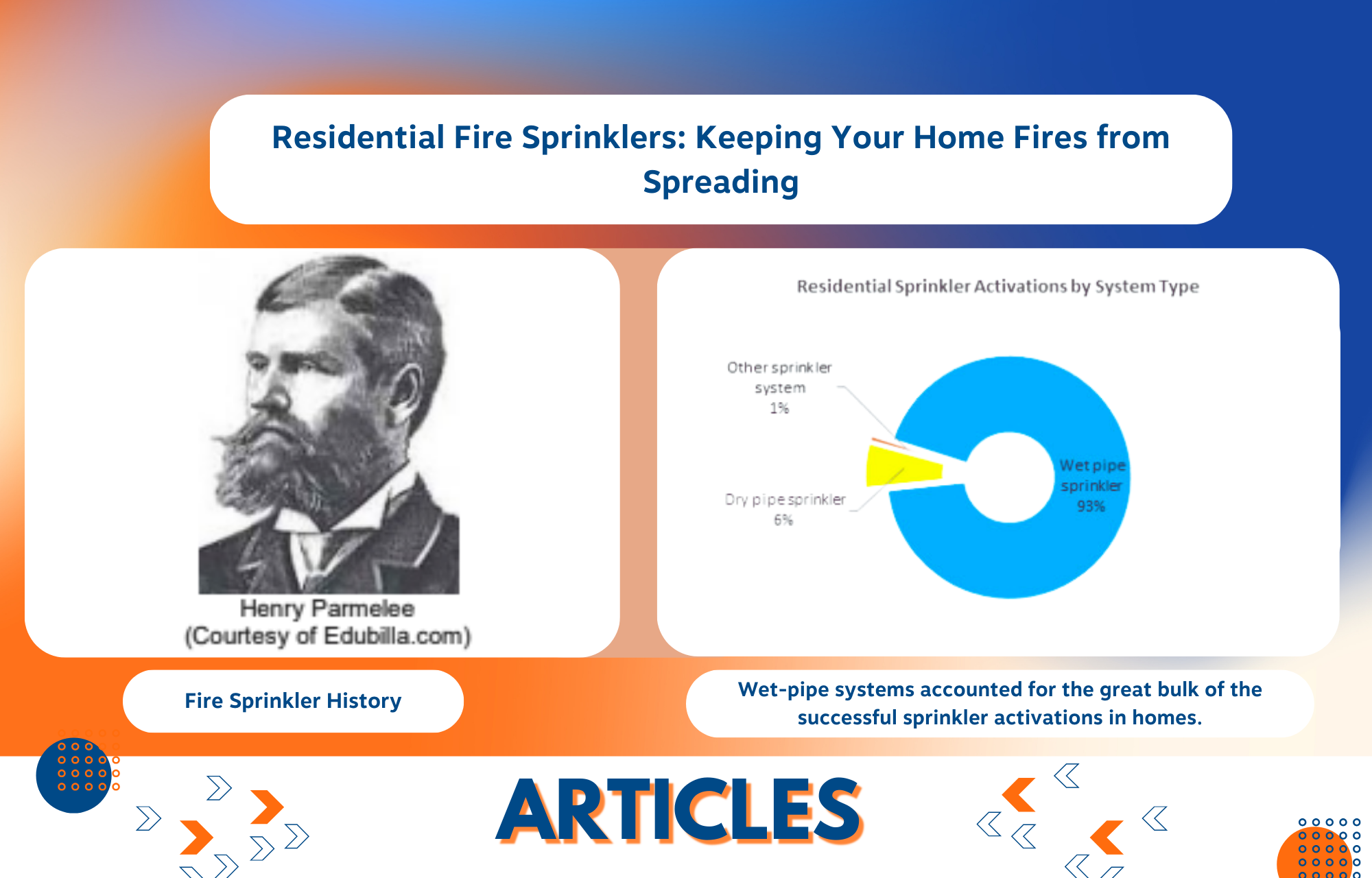

Fire Sprinkler History

Fire sprinklers have been in use for a really long time. Ironically, 2024 marks the 150th anniversary of Mr. Henry Parmelee’s 1874 initial sprinkler invention. Remember your fire sprinkler history? Mr. Parmelee desired a tool to guard his Connecticut piano manufacturing against a fire.

The National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control released a study titled America Burning (1) in 1973. Finding strategies to lessen the detrimental effects of fire in the US was the aim. “The proposed U.S. Fire Administration supports the development of the necessary technology for improved automatic extinguishing systems that would find ready acceptance by Americans in all kinds of dwelling units,” was one of the ninety recommendations made by American Burning (2).

Fire sprinklers had been in use almost a century when America Burning was published, but they were mostly used in commercial buildings where their goal was to lower property damage and business interruption. America Burning presented a novel idea: fire sprinkler systems stress life safety.

Along with the America Burning study, the technical committee on automatic sprinklers of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) designated a subcommittee to create a fire sprinkler installation standard for one- and two-family dwellings. “The basic design objectives for the dwelling sprinkler system were to be inexpensive and provide: (1) a system that would allow the occupants sufficient time to ensure their survival,” said Third

Fire sprinklers in one- and two-family homes, as well as mobile homes, now follow NFPA 13D as the installation guide. It initially came out in 1975, and the first iteration made use of conventional sprayers. Working under federal financing, the Factory Mutual Research Corporation (now FM Global) developed and tested a residential sprinkler employing quick-response (QR) technology. These sprinklers ran almost five times quicker than ordinary ones.

Two full-scale tests in 1979 and 1980 helped to confirm this technology. Fire sprinklers were a construction and fire code requirement for newly constructed schools, public gathering places, apartment buildings, hotels, and health care occupancies over the decades of the late-1900s. The focus in these occupancies was primarily on life safety, where conventional sprinkler protection in factories, manufacturing, industrial, office, and mercantile uses was directed more toward property protection or avoiding business interruption.

NFPA published NFPA 13R, a low-rise residential building standard, in 1989. Up to four stories in height, NFPA 13R was something of a hybrid between NFPA 13 and NFPA 13D that let hotels and apartment buildings integrate property protection with life safety.

Residential Fire Loss

The United States records over 500,000 structural fires annually. Approximately 375,000 (roughly 75 percent)

Of these, structural fires strike homes. One- and two-family homes, apartments, townhomes, dorms, motels, lodging houses, condos, and barracks; homes and sleeping quarters for individuals.

Residential occupancy has been responsible for 76 percent of the fire deaths, 77 percent of the fire injuries, and 71 percent of the structural fire loss over the past five years.

Residential Fire Sprinklers Versus Commercial Ones

It was understood that the research and testing conducted in the 1970s had produced a home sprinkler that had to operate differently than the traditional fire sprinkler in use. First of all, the composition of a normal home room was different from most rooms in a commercial building. In commercial buildings, most of the furnishings—the objects that can burn—are found more in the middle of the space; in residential settings, the furnishings typically lie near the outer walls. To do that “wall-wetting,” the household sprinkler has to send water higher.

Furthermore, occupant tenability had to be taken into account in order to offer the needed life safety gains; hence, separate testing and listing standards were devised. Fire sprinklers had been tested and listed in nationally acknowledged testing facilities, including Underwriters Laboratories (UL), back in the early 1900s. UL 199 is the standard applied for fire sprinkler testing and listing. Originally, UL 1626, the standard used for testing and listing residential fire sprinklers, has now been included in UL 199.

A listed residential sprinkler must satisfy specific requirements, including a full-scale fire test. Only one or two sprinklers must work rapidly enough in that test to restrict temperatures at both the ceiling and at eye level to tenable conditions.

Faster activation has also been found over the years to produce fewer hazardous fire gases, particularly carbon monoxide (CO), therefore enhancing occupant survival.

Residential Sprinkler Shipments

Since 2000, the NFSA has tracked shipments of home sprinklers. Trending higher, residential sprinkler shipments now account for roughly 25% of all fire sprinklers imported into the United States.

Residential Sprinkler Performance and Effectiveness

Both NFPA 13D and 13R drew considerably on data analysis. Both criteria excluded fire sprinklers in places where fires were unlikely to start and, should they start, fire growth would be limited and would have a minimal detrimental effect on the residents. The information from past studies is included in the following table, along with modern fire statistics.

For the current five-year period of 2018–2022, NFSA examined household sprinkler performance and efficiency. Of all the effective sprinkler activations (56%), they happened in residential occupancies; the activations are broken out here:

- Apartments and multifamily homes: 41 percent

- Hotels and motels: 5%

- One and two-family homes: 5 percent

- Other residential (dorms, hotels, etc.): 5 percent

Wet-pipe systems accounted for the great bulk of the successful sprinkler activations in homes.

Here is a breakdown of the type of residential property among the ones where sprinklers ran and proved efficient:

Of the 8,202 fires in residential occupancies where the sprinklers were judged effective, one or two sprinklers controlled the great majority.

Although a small number of sprinklers were effective in suppressing household fires, the sprinklers kept the fires limited to the area of origin or room of origin 92 percent of the time.

Where do most residential fires under sprinkler control take place?

These are the ten most often occurring locations in residential occupancies where sprinkler-operated fires occurred; these account for 85% of all sprinkler-operated residential fires:

Summary: More people die and are injured in residential structures fires than in all other kind of fires. Furthermore, they are accountable for more than 70% of the structural fire damage in the United States. The early 1970s America Burning Report advised on the construction of residential fire sprinklers. That report led to the development of standards and home sprinklers, and the model codes began to demand they be installed.

It has been demonstrated that automatic sprinkler systems help to effectively suppress fires in homes’ occupancy rates. One or two sprinklers are turned on in the great majority of sprinkler-activated house fires. Once set on motion, sprinklers carried the fire, 92 percent of the time, to the object of origin or room of origin.

References

[1] America Burning: The Report of The National Commission on Fire Prevention and

Control” (PDF). U.S. Fire Administration. Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 4, 1973.

[2] Ibid., Recommendation 75, page 170.

[3] Dr. John Bryan, “Automatic Sprinkler and Standpipe Systems” (Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association, 1990), page 371.

Courtesy: J.Nisja, with NFSA.